How hard has the pandemic hit your family?

The pandemic has fallen on our society like rain on a staircase, running more easily off the privileged top steps and deluging the families on the lower rungs with a flood of accumulated intensity.

Walking through wealthy neighborhoods adjacent to the area where we lived in the Spring of 2020, it became clear how many of those mansions were empty. The rich had moved to their vacation homes to shelter from the coronavirus storm. In a similar neighborhood, my sister’s friend served as a nanny to a family of great means. Since the pandemic hit the United States in February, the nanny has been the only person to leave or enter their home.

In contrast, the mother of a child who attends a school I serve in North Philadelphia did not have a choice to stay home, no matter how scared she was of getting sick. In order to keep her family above the poverty line, she couldn’t afford to stop going to work as a home health aide. She risked contracting the virus multiple times and still continues to leave the house to fend for her family.

Easier access to health care and childcare expands the divide between the “haves” and the “have-nots.” Small but significant resources make an enormous difference, like having access to nearby medical offices and having stores in your neighborhood who are willing to deliver food and supplies to your doorstep.

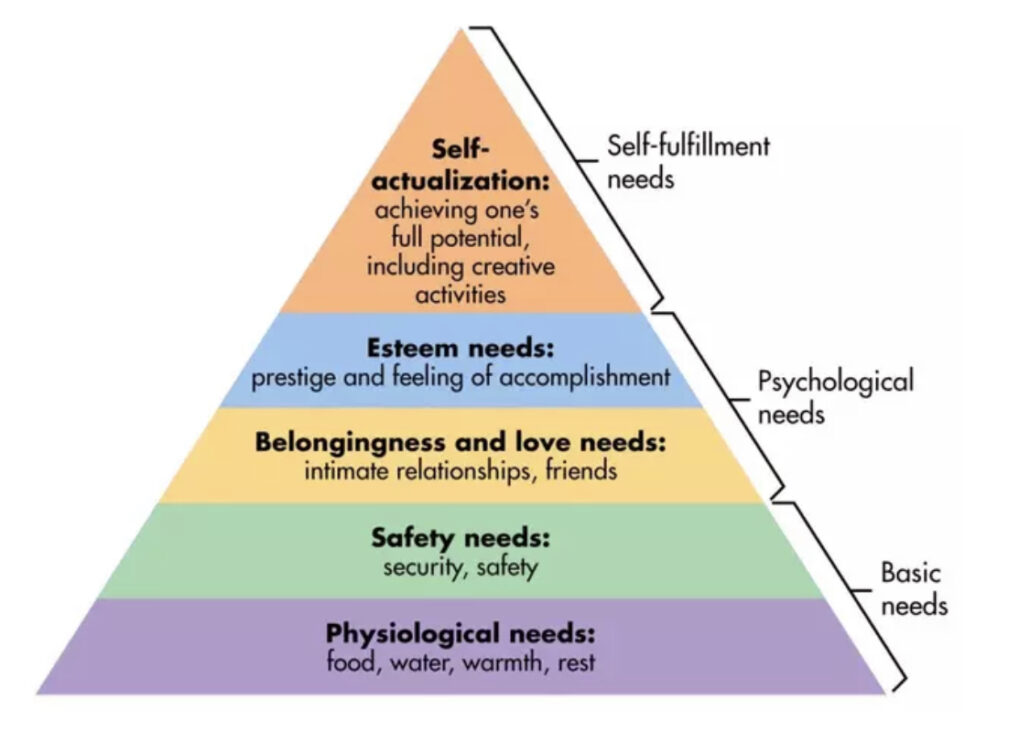

In an effort to understand the inequity during this health crisis, I recalled how Abraham Maslow (1943) observed that individuals must satisfy lower level “deficit needs” before progressing on to higher level “growth needs.” Essentially, you worry about food and shelter before wifi. He described this social phenomenon in a hierarchy of needs:

In the last 10 months, families with less money and resources have spent much more energy meeting their basic needs. Maslow’s framework can explain why some felt safer than others in 2020 going to the store or sending their kids to school in the face of the health crisis. But this hierarchy of needs had limits. For instance, it did not help me understand:

- why George Floyd’s and Breonna Taylor’s murders changed the world for some of us but didn’t make a dent in others’ lives.

- why the economic impact of the pandemic triggered a “she-cession” that hit women, especially working mothers, harder than others.

- why we witnessed such a close election to decide who would lead the country out of intertwined economic, social, and health crises.

I needed more than a hierarchy of needs to explain what I was observing. So I added a lens of social privilege.

What is privilege?

According to Wildman and Davis (1995), an important first step to understanding the concept of group-based privilege and how it can shape peoples’ perspectives, experiences, and interactions is to examine our own experience. We can be a beneficiary of privilege without recognizing or consciously perpetuating it.

Take me, for example. Although I am not a member of the socially privileged group based on my religion (I’m not Christian), I belong to many favored social groups. My ethnicity, race, gender identity, ability level, and sexual orientation give me advantages and make life easier for me.

As an (1) American (2) male who is (3) white, (4) middle class, (5) cis gender, (6) straight, and who possesses a (7) high level of ability, I have access to education, social acceptance, and resources. My social status allows me to move through the world with more ease. I don’t have to spend as much energy as many other people to meet my basic physiological and safety needs.

For instance, if I need to walk to the store after dark, I don’t feel the fear that I might if I was trans, female-identifying, and/or a Black or Indigenous person of color (BIPOC). My social status gives me the privilege not to have to feel a constant fear of harassment, emotional abuse, or the threat of violence.

Feeling safer because of this social status, even just thinking about privilege, used to be an academic exercise for me. A year ago, it was a “social construct.” Now, the pandemic has brought this lens to the forefront of my awareness, revealing who is at the most risk in our society.

This last year has also revealed an ugly side of living with social privilege: the more you enjoy, the less empathy you display. When you decide whether or not to send your kids to school, to eat in a restaurant, or to travel freely, your decision is heavily influenced by your privilege. These choices also have an impact on others in your community.

How does privilege intersect with empathy?

Privilege gives us the choice to feel empathy for our neighbors.

One example is the resistance to wearing masks in public: in my own daily life, I often observe families where the women and children are all wearing masks but not the grown men. At first, I assumed that men were afraid of appearing less masculine. I later learned that men were more resistant to mask-wearing because, as a group, we suffer from an empathy gap (Reader, 2020). Preliminary findings from a Boston College study revealed that men “had less confidence in science and they had less empathy towards people who are vulnerable or in high risk categories.” Although this behavior has been politicized, the science has been clear that wearing masks limits the transmission of the airborne coronavirus.

How comfortable you feel when you challenge a stranger’s behavior also depends on your social status and privilege. As a middle aged cis white man, I am less likely to be challenged in everyday interactions than a younger person, a woman, or a BIPOC person. We grant a license to more privileged social groups like cis men to behave with impunity, especially during a health crisis. We use maxims like “boys will be boys” to explain away the social restriction to calling out dangerous behavior perpetrated by the privileged class.

The empathy gap goes both ways. Not only do people with more privilege fail to empathize with members of their community who live with less but people with less social privilege also make decisions that show how unsafe they feel.

For example, Black and Brown Americans show a distrust for a health system that has favored white Americans and provided consistently poor care and inadequate resources to their families. This distrust negatively impacts their decisions about health initiatives like seeking out routine medical care or getting vaccinated for COVID-19. Who loses? Not just Black and Brown families. When we can’t reach a critical mass for vaccination against a global pandemic, all of us are put at greater risk.

To accompany Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, I envision another pyramid showing that greater access to resources depends on your gender, whiteness, wealth, and race. A “Boys-Will-Be-Boys” Hierarchy of Privilege would make it easier to understand the depth of BIPOC distrust with the medical community or the disproportionate risk that factory workers, educators, and food service workers have endured in the first ten months of the pandemic.

What can we do?

The response to a deficit in empathy is community building. On the simplest level, we build empathy by seeing the world through another person’s eyes, by understanding their fears and hopes and desires at a deep, emotional level. You and I can start a meaningful conversation if I feel safe to express my current needs (Maslow, 1943) and can ask what current needs are draining your energy. But where is a safe place for us to listen and share our personal experience?

Imagine a cross-section of the people in your community seated in chairs arranged in a circle at your local school or house of worship. Listening circles have been used throughout history by indigenous cultures to reach consensus. More recently, this practice has gained traction as a restorative justice alternative to criminal proceedings and has even been used in response to the Catholic Church’s sexual abuse scandal. The most exciting development is the use of restorative circles to build community in classrooms.

Imagine a listening circle where we can become more aware of the privilege that we each enjoy and hear how the lack of privilege may limit another person’s movements through their daily life. One powerful product of these listening circles would be increased empathy.

This won’t be our last pandemic, economic crisis, or sharply divided political era. In times when we depend on each other even more, we need to build a stronger, more interdependent community. We need each other to get through these challenges.

How can we leverage our civic, religious, and educational institutions to create such listening circles?

REFERENCES

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-96.

Reader, R. (2020). The real reason why some men are still refusing to wear a mask. Fast Company magazine. Retrieved from: https://www.fastcompany.com/90544483/the-real-reason-why-some-men-are-still-refusing-to-wear-a-mask/

Wildman, S. M., & Davis, A. D. (1995). Language and silence: Making systems of privilege visible. Santa Clara Law Review, 35(3), 881–906. Retrieved from: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview/vol35/iss3/4/

0 Comments